What Did Kendall Nash Say About His Family

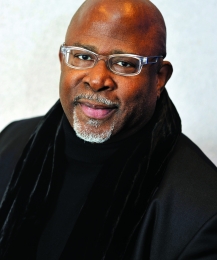

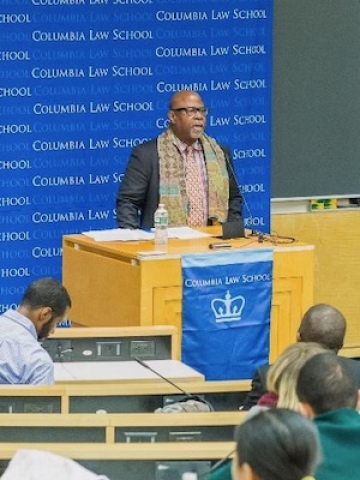

For Kendall Thomas, Nash Professor of Law and a co-founder of the Center for the Study of Law and Culture at Columbia Police Schoolhouse, the COVID-nineteen pandemic is a teachable moment.

"Intellectually, I take filtered the last four months through one of the central concepts of U.S. ramble law that sits at the centre of the doctrine of federalism and its division of sovereignty between state and local governments," says Thomas. "Information technology'southward the doctrine of police power, and the power of country and local governments to enact laws and policies and promulgate regulations that are aimed at protecting 'the health, safety, welfare, and morals of people' within a given jurisdiction—which embraces everything from criminal law to health laws."

Equally a scholar of comparative constitutional law and human rights, Thomas saw "a clash betwixt two different dimensions of police power" in May and June as demonstrations protesting police violence and systemic racism swept the nation while social-distancing regulations were in consequence in many places. "From one perspective, the police power principle embodies a positive idea that speaks to the affirmative obligation government has to protect the public health, condom, security, and welfare. On the other hand, in many communities of color in this state, the police power is seen as a negative, repressive, and fifty-fifty fierce presence. That'south because the face of police power for these Americans is the police who are their principal point of contact with authorities and the law. Hasn't their history in this state taught them that the vehement taking of Brown and Blackness lives is an essential function of the work that constabulary exercise in their communities."

Thomas says the current protests confronting law brutality are in effect a demand to end police ability as we know it. "For me, the COVID-19 pandemic and the newly energized motility confronting law violence have thrown the tension between these two visions of the police ability and American life into stark relief," he says. "How do you reconcile that tension? That'southward not just a contradiction of the police power and our constitutional law but of American life."

A Call to Action

Thomas understands why and then many people are willing to risk exposure to COVID-nineteen past participating in demonstrations (although, as a human in his 60s, he has chosen not to have that chance himself). "The conclusion to have to the streets is driven by anger, yes, but it also reflects a calculated balancing of risk that I am not prepared to dismiss as irrational," he says. "Exercise they fear this invisible virus more than the visible, violent reality of life under a necropolitical regime that normalizes the state-sanctioned taking of Brown and Black lives?"

Thomas is encouraged by young activists who are building a civic consensus among people between eighteen and 30 that "voting is a revolutionary human action." Voting, he says, "is the most immediate and important affair we need to do" in order to harness the momentum of the street protests and then that it can lead to sustainable institutional and social change. "I was built-in in 1957, so I'm of a generation where I remember people talking about the right to vote and exercise of the franchise in precisely those terms—as a practise of liberty, equally a revolutionary need," he says.

When the landmark Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, Thomas was 8 years one-time. "Well, 1965 and 2020 are beginning to look a lot alike with the rise of illiberal anti-democratic counterrevolutionary politics that is seeking to turn the clock back. The constabulary and the courts have been weaponized in a campaign to suppress, undermine, and, if possible, eliminate meaningful access to the voting berth for Black and Latinx Americans," he says.

Activism as a Manner of Life

Thomas grew up in a community of activists in Oroville, California, located at the base of the Sierra Nevada foothills. He sang in the choir of the church where his grandfather was the pastor. He remembers wearing a black armband subsequently the 1963 assassination of civil rights leader Medgar Evers and marching with his grandfather'southward congregation from the church building to the courthouse for a acuity.

Afterward earning his B.A. (in English literature and theater studies) and J.D. from Yale, Thomas arrived at Columbia in 1983 equally an associate in law and joined the kinesthesia the following twelvemonth.

At the fourth dimension, "Columbia was a very unlike identify with many fewer women and people of color in the student trunk and on the faculty, and the schoolhouse was much less international," he says. "When I arrived at Columbia, the central and shaping reality of American legal culture for those of us in my generation who were gay or lesbian—whatever our race, ethnicity, or nationality—was the knowledge that we were inbound the profession at a fourth dimension when it was nonetheless a felony punishable with imprisonment in many places in the country to engage in consensual sexual intimacy with someone of the aforementioned sex," he says. "Then I entered police teaching quite conscious of the fact that I was breaking the law in a way by my very existence and participation in public gay sexual culture." This history, he notes, is why LGBTQ+ students—at Columbia and at other police schools—called their affinity group OutLaws.

Thomas says being a gay Blackness homo gave him a perspective that feminist scholars describe equally an epistemological standpoint. He says his legal education taught him that the law is a tool for protecting people and providing a procedural and institutional framework for human being flourishing. "My lived feel taught me that the constabulary was a necessary simply bereft tool for challenging the hierarchical social and political structures that privilege being recognized as white and heterosexual in this country and then many others," he says. "I accept taken that experiential perspective with me to the report of law and to my professional person practice every bit a legal critic."

A Progressive Scholar

One of the smashing influences on Thomas' life was Kellis Parker, who, in 1972, became the first Black professor at the Law Schoolhouse. "Kellis taught me that my work as a lawyer is a calling," Thomas said at Parker'south memorial service, in 2001. "The dominant perspective sees the legal educator every bit a problem-solver, whose role is to justify the police force; Kellis challenged me to see myself as a trouble-poser, whose job is to criticize the law and law'southward complicity in justifying illegitimate privilege and ability."

Thomas has practical that philosophy to his work throughout his career, including in his AIDS activism showtime in the 1980s. Thomas served on a Columbia University task force to advise on policies regarding HIV/AIDS and went on to be a founding member of the Bulk Action Conclave of ACT Upwardly, Sex Panic!, and the AIDS Prevention Activity League. He as well served as vice chair of Gay Men'southward Wellness Crisis and recently completed a seven-year term on the board of the New York City AIDS Memorial.

Thomas has taught and written extensively about disquisitional race theory, legal philosophy, feminist legal theory, and constabulary and sexuality. He has collaborated with colleagues, including Kimberlé Crenshaw, Isidor and Seville Sulzbacher Professor of Law, who coined the term "intersectionality" in 1989. She and Thomas were authors and co-editors of the seminal 1995 book Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement.

An Integrated Life

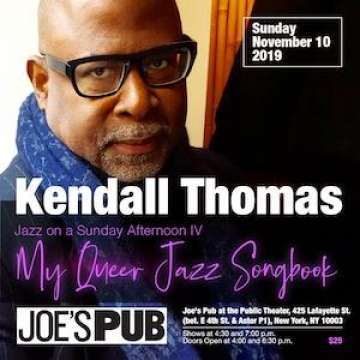

1 yr ago, as the earth celebrated LGBTQ Pride Month and the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots that launched the modern gay rights move, Thomas took the phase at Joe's Pub—a renowned music venue at the Public Theater in Greenwich Hamlet—for his show "Summertime–A Solstice Songbook."

Thomas's appearances at Joe'due south Pub, where he's performed since 2017, are both political and personal statements. In 2018, he performed a show about the music of Nat "Male monarch" Cole. "I talked virtually how much he had contributed to the cultural politics that prepared the ground for and was aligned with the Blackness freedom and civil rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s," says Thomas.

He has also brought the arts into his work on the law. Some years ago, he wrote and presented an evening of music and theater at Columbia's Miller Theater in which police students, staff, and faculty collaborated with professional actors in a operation slice on the culture of homo rights. And he collaborated with choreographer William Forsythe and the Forsythe Company on "Human Writes," a performance-installation that was staged in Belgium, Germany, Sweden, Turkey, and at the United nations' Palais des Nations, in Geneva, Switzerland.

Thomas says condign a late-in-life functioning artist has been empowering. "Information technology's made me feel whole and integrated. Living an integrated life is more important than information technology's ever been because the challenges that lawyers face are as nifty as they've e'er been," he says. "At a time when the rule of law is nether neat stress, if we're going to be up to the job of defending the thought of the rule of law, nosotros have to lean into those parts of our shared lives that affirm our humanity. I am grateful to have found that affidavit in a powerful way through my return to the arts."

laniganquaecte1993.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kendall-thomas-takes-pride-being-outlier-and-outlaw

0 Response to "What Did Kendall Nash Say About His Family"

Post a Comment